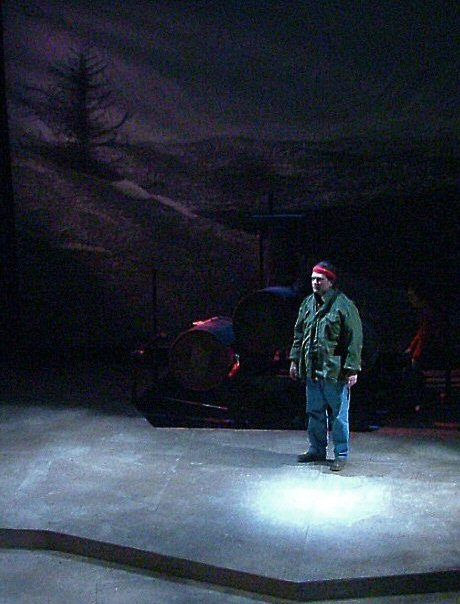

Judevine

Directed by Kim Bent

(2007 Production)

Click to see letter of recommendation from David Budbill, playwright

Lost Nation Theater (Montpelier, VT)

April, 2007 (Remounted September, 2008)

David Budbill's Judevine is a verse play that looks at a drab, impoverished town in rural Vermont and at the people who inhabit it and give it color, humanity, and beauty. The lighting design reinforced this by using a monochromatic palette that was occasionally punctuated by moments of more saturated color.

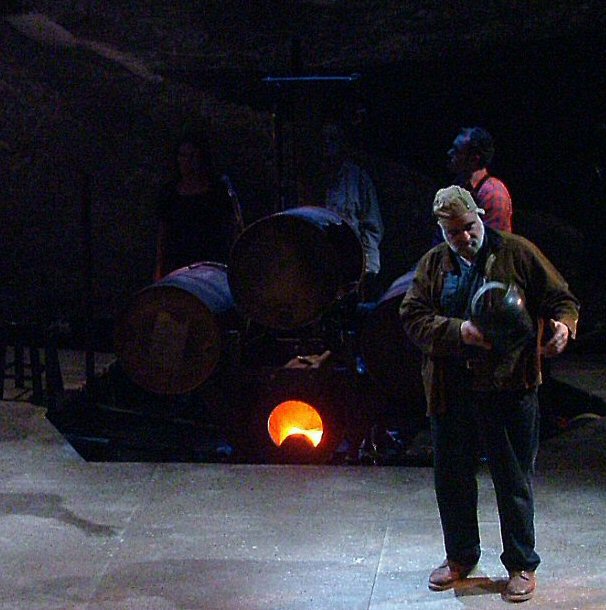

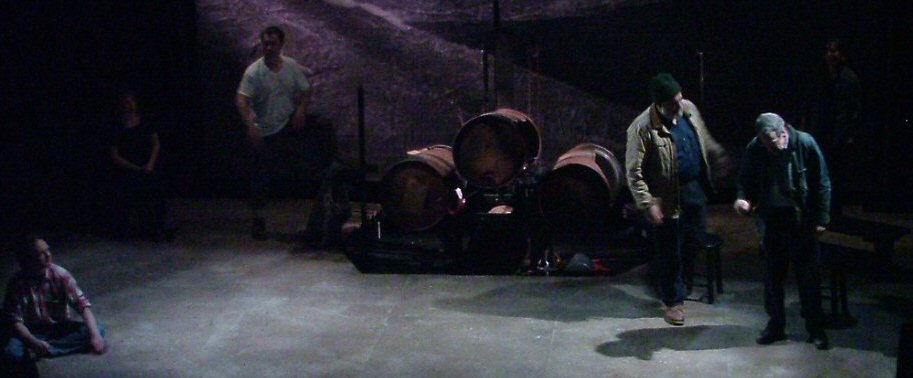

The script of Judevine calls for all sound effects to be actor-generated; in Lost Nation Theater's production, this was done through use of the Judephone — a percussion instrument constructed from found objects including oil drums, steel pipe, and other pieces of metal. The Judephone furnished, at various moments, bells and chimes, thunder, engine sounds, and other effects for which there is no name.

The Judephone also was used as a visual metaphor, serving as an oil-fired heater a welding bench (the fire and welding effects being done entirely with light), a beer cooler, and a cathedral, as well as its use as a piece of scenery and an acting position. Various lighting fixtures were mounted within, or focused on, it to reinforce the various images.

"Salzberg always asks interesting questions that inspire a positive, productive creative dialogue with all members of the production team." -- Kim Bent, Founding Artistic Director

"A suggestive backdrop...along with creative light by Jeffrey Salzberg and realistic costumes...all come together to create the bleak but caring atmosphere."

"...Effectively dramatic lighting round(s) out the picture."

"The black-and-white backdrop...adds to the poetry, as it takes on shadowy, brooding dimension with the changing stage light."

Ohio, Revisited

Written and Directed by Cara Scarmack

The Roadsters (New York, NY — Performed in Burlington, VT)

August, 2012

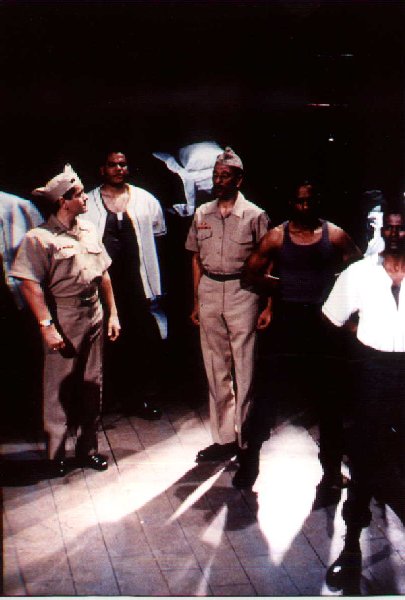

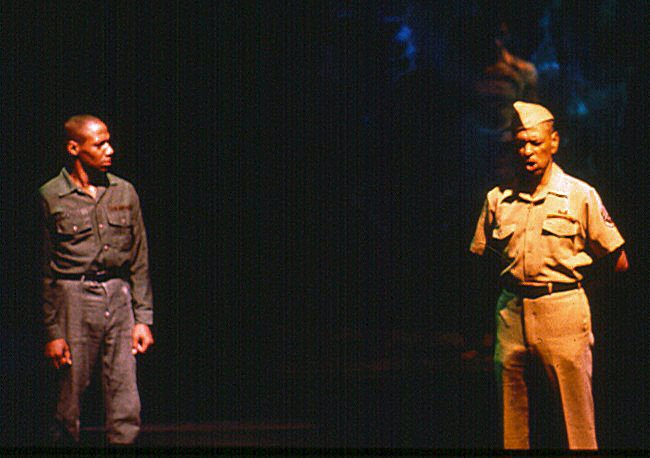

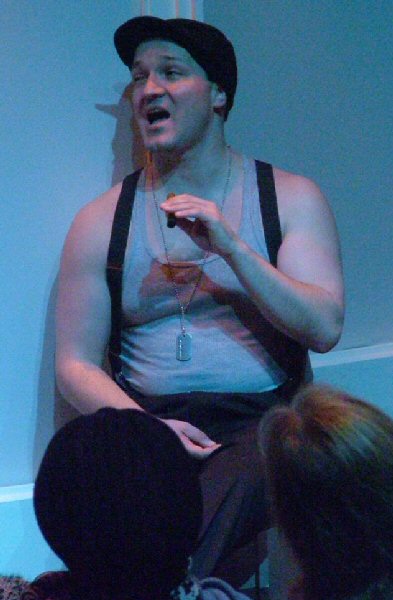

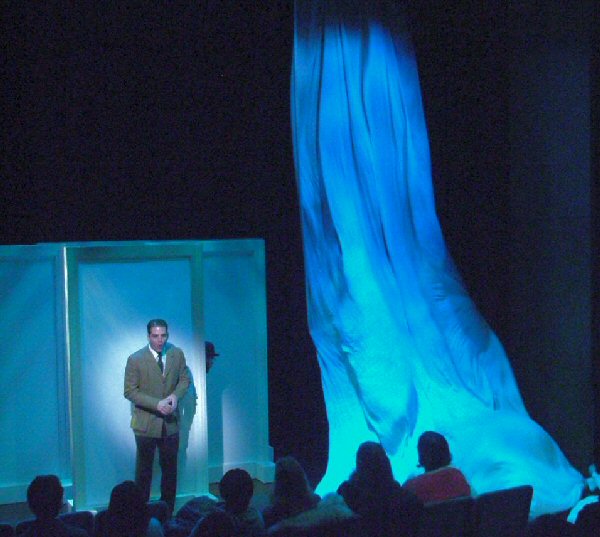

A Soldier's Play

Directed by Eileen Morris and Alex Allen Morris

(2007 Production)

Click to see letter of recommendation from Eileen Morris, director

Ensemble Theatre (Houston, TX)

May, 1994

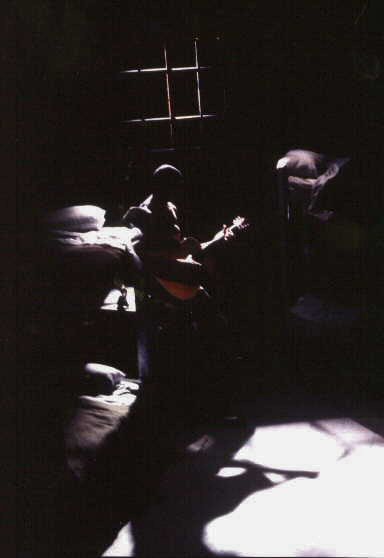

Charles Fuller's Pulitzer Prize-winning A Soldier's Play is the story of the investigation into the murder of a Black army sergeant in 1944. The plot develops through closely-interwoven flashbacks and "real-time" scenes, the transitions between which were handled by the lighting design, augmented by minor changes in costume and sound.

The lighting designer's concept was based on articulation, specificity, and detail. The finished design was extremely fluid, with some cues sharply defined while others flowed smoothly from one to another. The lighting designer used scenic elements symbolically, notably the barracks window, which was used as a visual metaphor for the manner in which Black soldiers in the segregated army were figuratively penned in and prevented from full participation, and the captain's office, which was often dimly lit even when empty to symbolize the omnipresence of the power structure which did not allow these soldiers to serve their country in the same ways that others were able to do so.

The lighting for the "real-time" scenes was starkly realistic while the flashback lighting was impressionistic; for example, while no attempt was made to precisely reproduce the lighting one might have found at night alongside a 1944 rural Louisiana roadside, the general feeling of such a scene was created with color, angle, intensity, and pattern. Since the flashbacks are dramatizations of various characters' accounts of the story, the lighting designer presented those scenes as filtered through those characters' memories, primarily through subtle use of projected patterns and saturated colors. As the tension in the plot heightened, the lighting became starker and more shadowy and the color saturation increased.

The Ensemble Theatre is the largest professional African-American theatre in the southwest and was selected by the editors of the Houston Press as the best theatre in Houston, over such better-known companies as the Alley Theatre.

A Soldier's Play was hung, focused, cabled, and colored in approximately 50 work-hours. The theater's lighting positions were extremely difficult to reach and several positions had to be rigged from scratch. As the facility had no permanent stage circuitry, each fixture had to be cabled directly to the dimmer packs. Approximately $80 was spent on materials, mostly gel and patterns. The show was operated by two electricians on three different consoles.

"...the play's shifting time frames (are handled) with clarity and precision, aided by the effective...lighting design of... Jeffrey E. Salzberg."

"...Jeffrey E. Salzberg's lighting and Winifred Sowell's set... were also pluses in a most enjoyable show."

"...A hard-working, efficient and knowledgeable designer...." -- Eileen Morris, Director

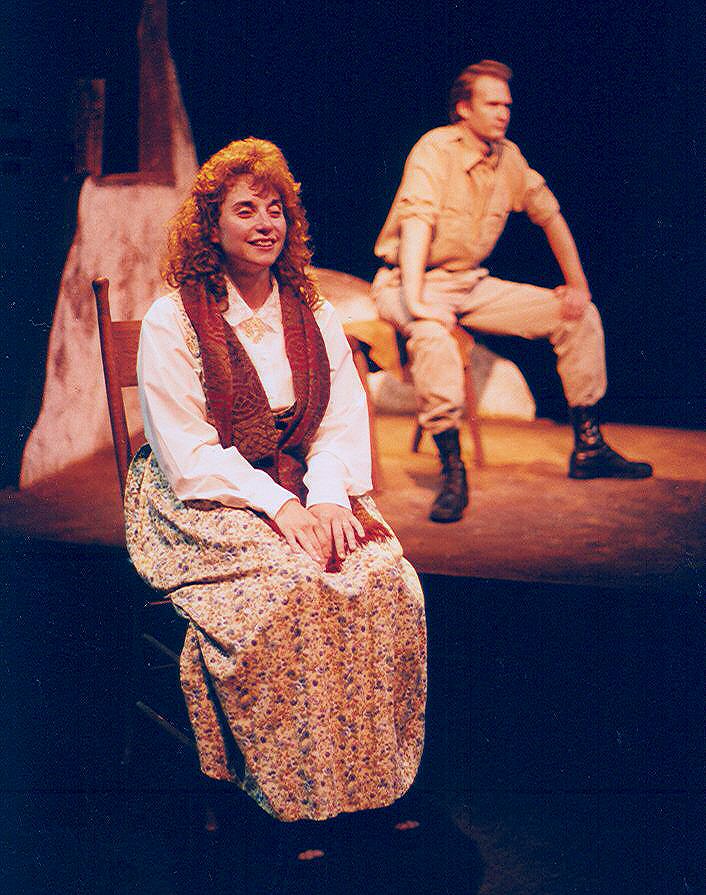

Woody Guthrie's American Song

Directed by Kim Bent

Lost Nation Theater (Montpelier, VT)

July, 2011

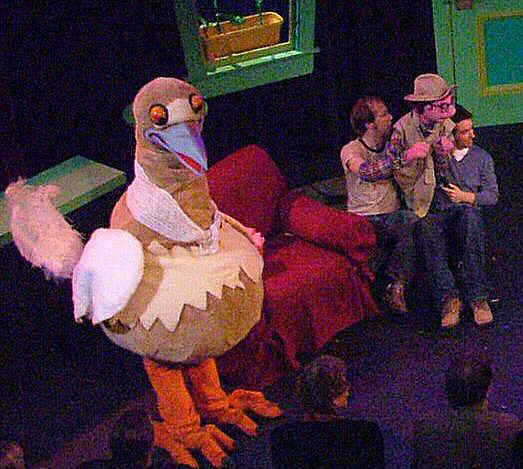

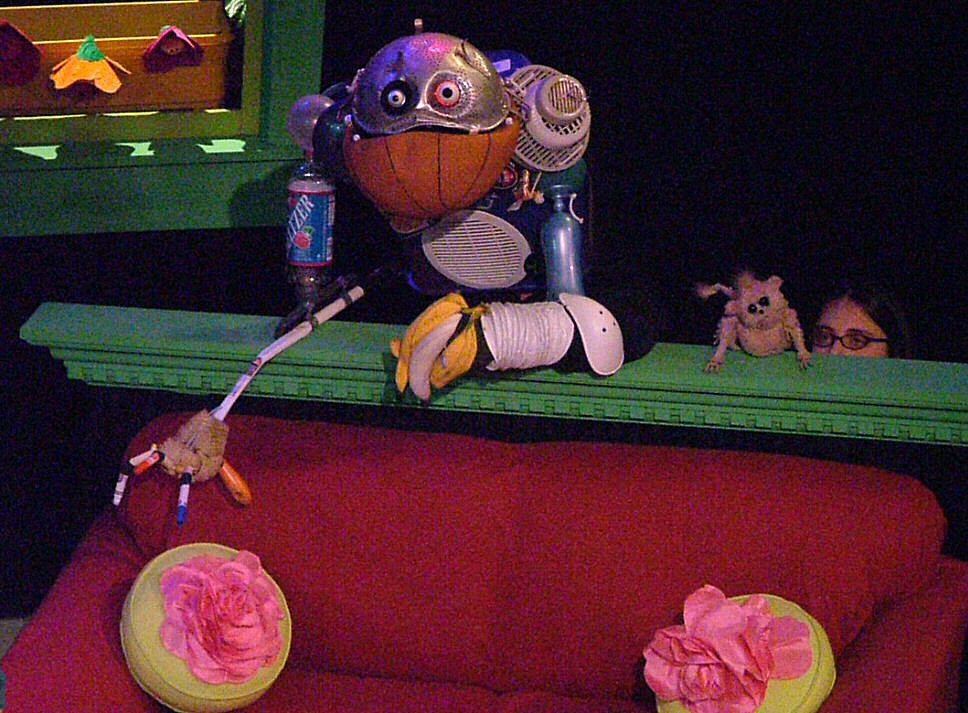

Pigeon Holed

Directed by Martin P. Robinson

(World Premiere)

Written by Annie Evans

O'Neill Puppetry Conference, performing at the West End Theatre (New York, NY)

January, 2006

Pigeon Holed, an irreverent look at the world behind the scenes of a successful children's television show, was written by 5-time Emmy winner Annie Evans and directed by Martin P. Robinson, the creator of the puppets for the original Little Shop of Horrors. Several of the human performers were cast members of Sesame Street and other children's television shows.

Pigeon Holed shared a mixed-repertory program with pieces by Heather Henson, Lindsey “Z” Briggs, Leslie Carrara-Rudolph, and others.

Shout! The Mod Musical

Directed by Keith Andrews

Click to see letter of recommendation from Chuck Tobin, Producing Artistic Director

Saint Michael's Playhouse (Colchester, VT)

July, 2013

Shirley Valentine

Directed by Douglas Anderson

Vermont Stage Company

(Burlington, VT)

March, 2012

"The simplicity and light of the production’s effects reinforce the mood and themes of Shirley’s narrative exploration."

"Jeffrey Salzberg's deft and evocative lighting...contributed to the show's polish."

Shortly After Takeoff

Written and Directed by Stuart Warmflash

Harbor Theatre Company, performing at Altered Stages (New York, NY)

March, 2006

"Production values are all splendid, especially...Jeffrey E. Salzberg's very effective lighting design."

The Great Divorce

Directed by George Drance

Based on the novel by C.S. Lewis

Magis Theatre Company

Theatre 315 (New York, NY)

January, 2007

"Production values are all splendid, especially...Jeffrey E. Salzberg's very effective lighting design."

This photograph was printed in the New York Times on 31 January, 2007.

The Cherry Orchard

Directed by Cathey Crowell Sawyer

Greenbrier Valley Theatre

(Lewisburg, WV)

October, 2014

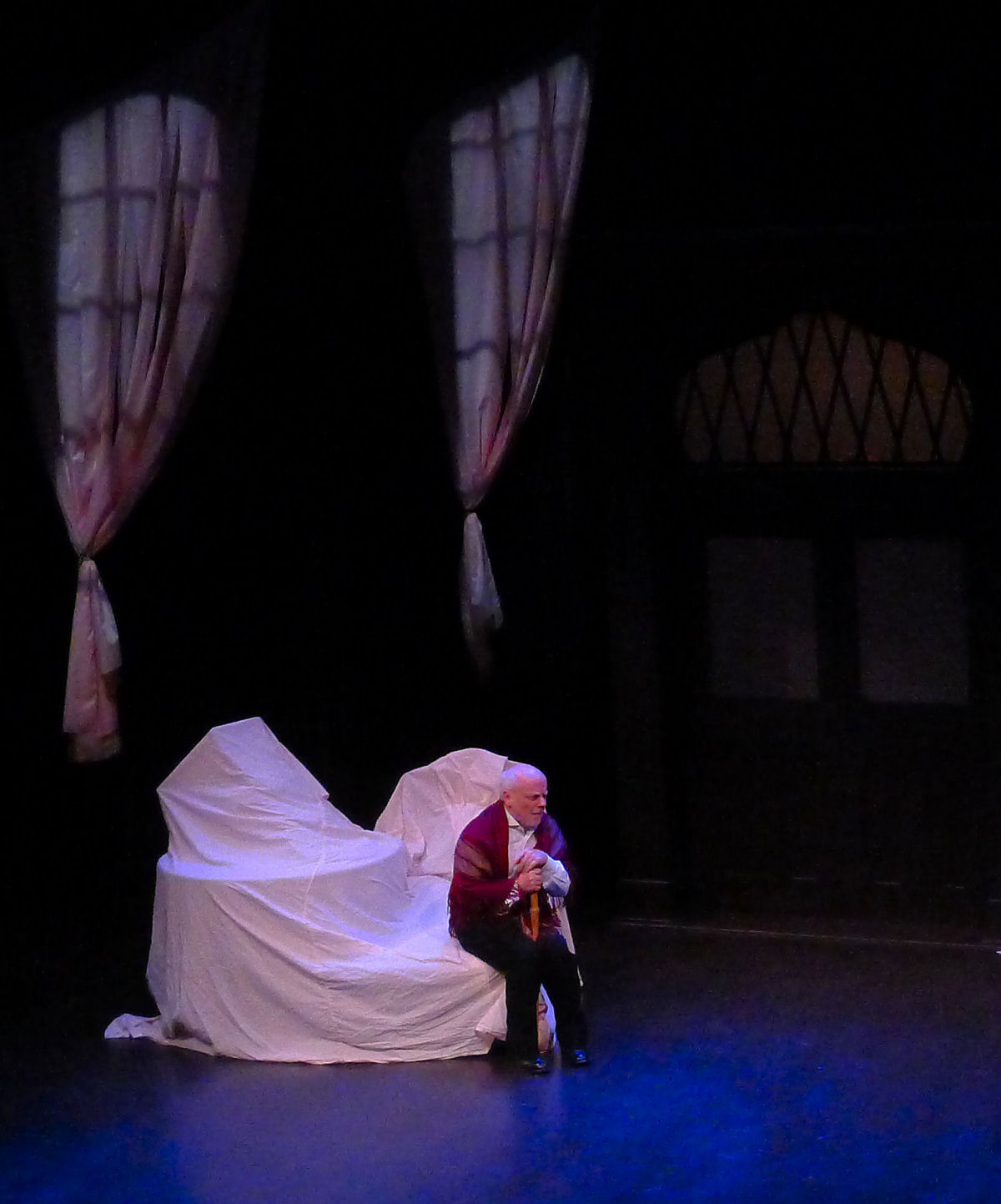

Molly Sweeney

Directed by Kim Bent

Lost Nation Theater (Montpelier, VT)

July, 2004

Brian Friel's Molly Sweeney examines the difference between "seeing" and "understanding". The play is a series of monologues by Molly, a middle-aged Irishwoman who has been blind since shortly after birth, her husband Frank, and Mr. Rice, the doctor who restores her sight.

Building upon the work of the scenic designer, the lighting designer provided each of the three environments a window, either reinforcing the set or creating the effect entirely with light, using these to contribute to the use of "vision" as a metaphor. Through a series of subtle changes beginning in Act II, the lighting became more and more stark, echoing the mood of the production, until the end, where the lighting isolated the character in metaphor as she was in life.

"Jeffrey E. Salzberg's lighting has the quiet task of stitching together the three distinct worlds the characters each inhabit, and keeping them all present for us as they individually present their story. The lighting sets clear moods without exaggerating them, giving the actors the prominence they deserve."

"The...pinpoint lighting by Jeffrey Salzberg...contribute(s)

to making this a first-rate production."

"Salzberg has been...adept and creative at accomplishing a fully textured design." -- Kim Bent, Founding Artistic Director

Molly Sweeney photographs by Kim Bent